Getting your eye in

This is the text of a speech given by author Danielle Wood at the Hobart launch of Breathing space

Back in the 1990s, when they briefly took over the world, I had a thing for Magic Eye pictures. Otherwise known as stereograms, they’re ones that show nothing of great interest if you focus on them, but that reveal – if you can manage to focus beyond them – hidden, three-dimensional images.

If you’re familiar with these pictures, you’ll know that there’s a knack to cracking them. It involves somehow relaxing your gaze but widening your eyes. It involves being extremely attentive while glazing over at the same time. Sometimes while you’re trying to ‘get it’, the pictures seem to flick between dimensions. You glimpse the three-dimensional image but can’t quite hold onto your perception of it. Once you do get it though, you almost fall into the picture; you wonder what on earth was keeping you on the outside of it.

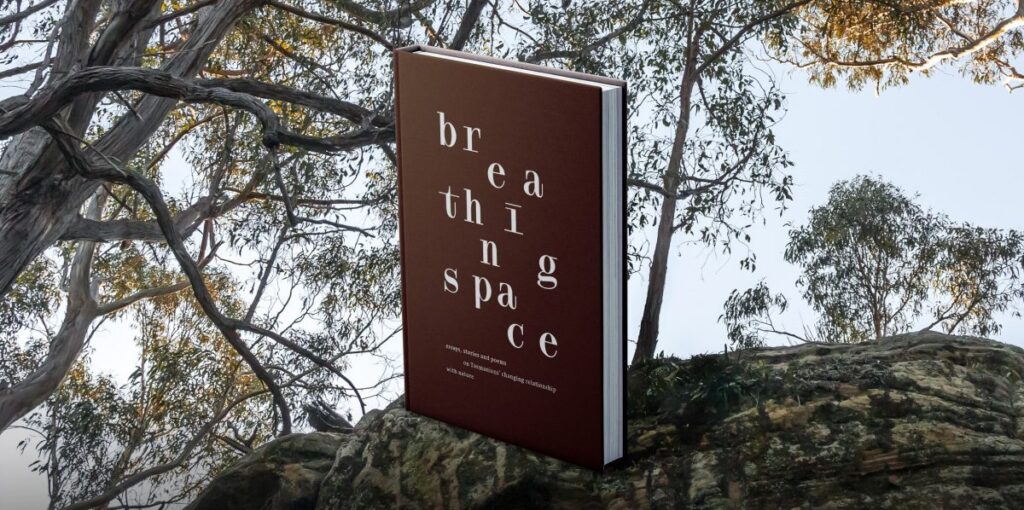

Before I tell you what I think this has to do with Breathing Space, let me tell you about the book itself. Published to mark the 20th anniversary of that excellent organisation, the Tasmanian Land Conservancy, it’s made up of contributions from more than twenty writers and artists, all of whom were responding to an open-ended brief delivered by editors Jane Rawson and Ben Walter. The brief was this: in 2020, while the world was being reconfigured by a virus, what were we thinking, and feeling – here in Tasmania – about our relationship with the natural world?

A range of genres is represented in the pages of Breathing Spaces, a range of styles, a range of perspectives. Despite the diversity, I think there is something that connects the dots, a thread that runs through the whole. And it’s the notion that to think about nature, and to represent nature in words or images, is at least in part a matter of developing a special way of seeing. Sometimes, this is a matter of being able to see beyond the surface and into the dimensions. Oftentimes, it’s a species of double vision.

This idea of special vision shows up in the very first piece, Keely Jobe’s exquisite essay ‘The Orchid Eye’. Keely writes: ‘Orchid chasing is equal parts wonder and attention. It’s a willingness to be charmed. Some call this “the orchid eye”. Others refer to it as “getting your eye in”, as if access to the world of orchids is less about detecting anomalies than it is crossing a threshold.’

In his essay, ‘The Urge to Order’ Peter Timms critiques the colonial vision of the Australian bush as unforgivably disordered, as he turns an investigative eye on the changing vegetation communities that surrounds his east coast Tasmanian property. In Greg Lehman’s essay ‘An Exceptional Future’, it’s a kind of Janus vision that the author asks us to develop, one that looks simultaneously back to the indigenous land management practices of the past and forwards to an imagined future in which the world finds a way to recover from the devastating impacts of the colonial and post-colonial eras. Double vision is important, too, in Jock Serong’s suspenseful memoir ‘The Shadows’, set in the Furneaux Isles, in which the author manages to see the remarkable beauty inherent in a deadly threat.

Some of the contributions to Breathing Space exhort us to see things we might have overlooked. Zoe Douglas-Kinghorn in ‘Sleeping Water’ asks us to take a look at our relationship with nature through the lens of socio-economic privilege. She writes, ‘Living in a single parent household and raised on Centrelink until I got my first jobs picking fruit and washing dishes, I didn’t have the time or access to camping gear to explore the wilderness’, before going on to explain how water pollution – although it seeps through everything – disproportionately affects those who live on low incomes.

Erin Hortle in her short story ‘The Currawong Shooter’ paints a picture of a complex web of competing priorities and makes us aware than any one way of seeing the world will prove insufficient. Ted Lefroy in ‘The Straight with the Curved’ writes about the importance of seeing land on its own terms, and not merely in terms of ownership or usage category. He writes: ‘Neither nature nor natural process respect lines on maps. The challenge is to move beyond the straight lines of the cadastre to also see land as a mosaic of watersheds, habitats and social networks’.

It is always the remit of the poet to give us new ways to see aspects of the world. And into the category of poet, I will squeeze Robbie Arnott, who, in his story ‘The Undertrees’ presents this extraordinary visual image of learning to see underwater: ‘For weeks I sat on the seafloor as the waves crashed above me, churning up my ceiling. When an extra set of eyelids glooped over my retinas I was able to see more clearly’.

Adrienne Eberhard in a breathtaking suite of poems called ‘Tinderbox Hills’ has permanently transformed my vision of the forty-spotted pardalote, a bird she describes as ‘a palm-full of the softest plumage,/olive and mossy/and running with pale spots/like a starry shawl/made for a dusky mouse.’ Pete Hay takes us on a road trip into territory both known and unknown, to a mysterious bunker, where he interrogates the motives of a man who ‘looked/and never saw/He did not imagine/that anything asked for his seeing;/that the land wanted reciprocity.’

James Dryburgh, in ‘Up the Creek’ gives us the sobering perspective that to see through our children’s eyes, in this time of rapid and terrifying change, may involve accepting that the places we see as degraded in comparison to our remembrances of times past, might be our children’s baseline for magical and authentic wildness.

How to see a way forward in the face of despair is a question many of the contributors to Breathing Space are circling. Others name it up. Peter Grant in his essay ‘The Dwindling Glades of Gondwana’ looks for a way to deal with his grief over the loss, to fire, of beautiful but slow-growing pencil pines. ‘What do we do?’ Grant asks. ‘We do what we would do if someone we love is facing illness or crisis: we keep loving them. And we get as much expert help as we can. But whether we are optimistic about their recovery has little bearing on our action.’

For my part, for the last essay in the book, I wrote about whether or not we will ever again see something that has, for the last 50 years, been hidden from view. Although Lake Pedder was drowned before so many of us had the opportunity to see it with our own eyes, we have nevertheless had the opportunity to fall in love with it through the visions of the artists, the photographers, the writers who captured it and handed it on to the future. Artists, photographers, writers: those species of folk who have, once again in Breathing Space, demonstrated the combined power of sensitivity, attention, talent, craft, time and care.

The primary note of this anthology is not joy, because the moment in time in which it is grounded is not a joyful one, even if fragments of happiness can be found within it. Perhaps part of the sadness that echoes through Breathing Space comes down to the fact that so many of us, for so much of the time we’re awake, have drifted so far from the natural world – from really seeing it, and from regularly understanding how fundamentally enmeshed we are within it – that we have come to need special ways of seeing just to catch a glimpse of reality.

If thinking and writing about nature requires us to get our eye in, then I think this collection would be a tonic for anybody who had somehow got their eye out. It offers not one but more than twenty lenses through which we might refocus – lenses that might help us in difficult or distracting times remember how to look beyond surfaces, and in multiple ways.

If we look in a slightly cross-eyed way at the anthology’s title, one in which words can flicker back and forth between nouns and verbs, we can ask ourselves whether it’s Breathing Space, a book about finding a space in which to breathe, or Breathing Space, a book about a possibly magical form of inspiration, remembering that from an etymological point of view, to breathe life into something is to inspire it. Or course, this anthology is allowed to be, and almost certainly is, both books at once – Breathing Space and Breathing Space.

Breathing Space is a fitting tribute to the Tasmanian Land Conservancy, which famously began life with $50 in the bank and is now one of the largest private landowners in the state. The brains and hearts behind the TLC were committed to a new way of envisioning conservation in Tasmania – a science-based, apolitical model that replaced reliance on the public sector with a broad-based DIY strategy of organisational networking and the channeling of philanthropic donations. Happy birthday, TLC. You are an inspiration to us all.

In closing, a brief personal observation.

When I read through the list of writers and artists whose have contributed to this book, I felt – even before reading a word – that I was in exceptional company.

The contributor list contains some of the people I regard as elders and mentors; it contains some of my most admired contemporaries; and it contains some of the people who’ve passed through my classroom, although to say I taught them would be an exaggeration, since my role, when it comes to people so talented, is only to recognise and encourage them. It also introduced me to some new writers, people whose works I will now look out for.

I’ve been proud and pleased, before, to have my work included in anthologies, but never so much, I don’t think, as I am this time. The contributors to this book, and the hard-working editors who have lovingly curated it, are writers, artists, seers, believers, doubters, questioners, dreamers and thinkers. In this book they have shown you what they see; in this book they have shown you how they see.

I wish this exceptional book well on its journey into the world.

Banner photo is of Rubicon Sanctuary, by Andy Townsend