Nostalgia

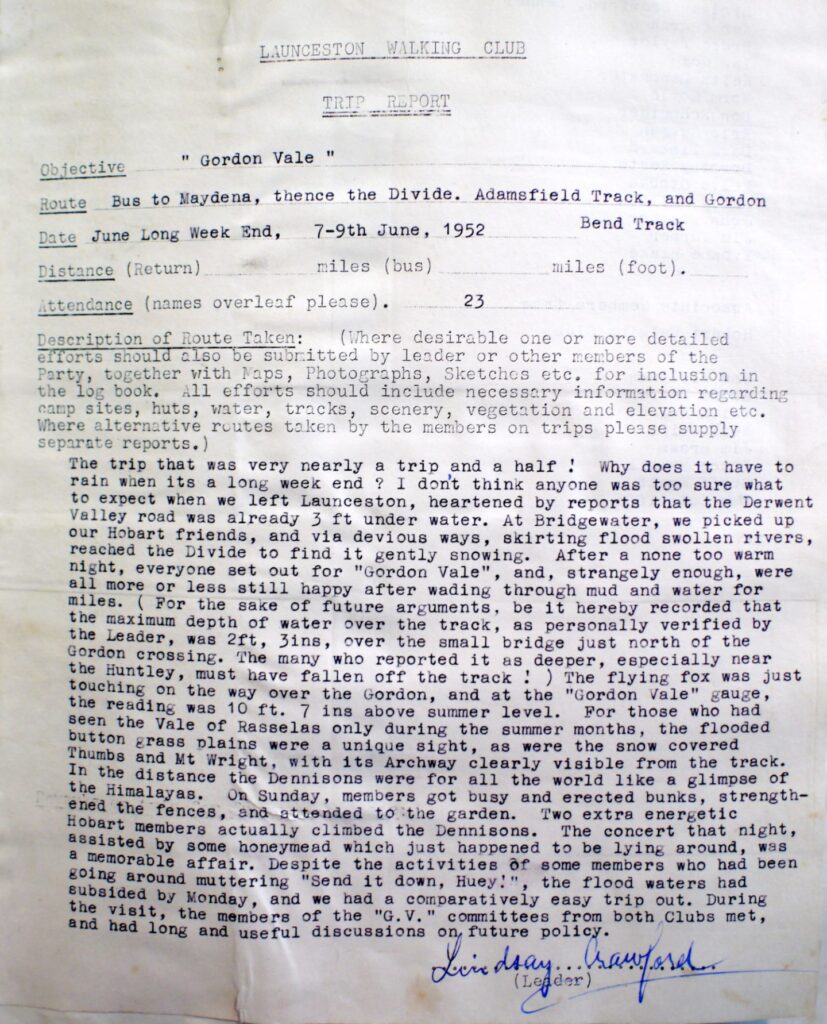

“Nostalgia” was written by Lindsay Crawford (b.14/9/1926 – d.2/6/2017) following a trip to Gordonvale in 1946, while studying for his Bachelor of Science at the University of Tasmania. It was published in the Student Union Magazine “Togatus” dated 7th October 1946, only a few months before the Launceston Walking Club (LWC) was founded in December that year. Lindsay subsequently led many LWC trips to Gordonvale. In 2016 Lindsay sent greetings to the LWC on its 70th anniversary and gave some background to his article (see below in author bio), and the article was then edited for the LWC’s Autumn/Winter 2019 “LANGANA” magazine. The Tasmanian Land Conservancy (TLC) thanks the LWC for sharing Lindsay’s story with us and for supporting nature conservation in Tasmania.

Gordonvale Reserve is a 81-hectare property in the Vale of Rasselas that was protected by the TLC in 2013 and continues to be managed for conservation.

Have you ever followed the wallaby tracks up the Rasselas Valley? Have you ever gone skylining in the far Denisons? Have you ever pushed through dense thickets of leatherwood trees, so white with blossom and so fragrant that you don’t believe they’re true?

About this time of the year, my view of the printed word gets interrupted with alarming frequency by a vision of high mountains, and I find myself longing for the rhythmical creaking of a pack on my back and the uneven feel of button-grass under my feet. I even yearn for a good healthy blister or two. When I should be swotting, I’m looking for dried apricots, or admiring the awful holes in my old socks. If you’ve ever been “up the Rasselas,” you’ll share my nostalgia. To be away from Tasmania is to hunger and thirst, hopelessly, for the sense of its mountain-country, and for the keen pleasure of being hot and tired and miles from your journey’s end, of sitting down to lunch with your feet in an ice-cold stream, and eating cold bacon and limp chocolate, and scooping anaspides out of your tea.

If you have experienced mountains only as a glory on the horizon, or as an abiding beauty at the back of a city, then borrow a pack and a sleeping-bag, buy some boracic and some bacon, and set off to revise your ideas.

I’ve been there once only. We left home in the rain, slept in the train at Maydena, to an orchestral accompaniment of thunder and splashing rain, and next morning took the Adamsfield track towards the wildeness. It goes through forest, over the shoulder of the Humboldt Range, opposite Tim Shea. If you take bikes as we did, you spend a half-day pushing up steep slopes and careering in terror down the other side. For a great part of our way, the soft drizzle of rain among the trees was mingled with a snowy drift of fragrant leather-wood petals. Then came a long dip downward to the floor of the Florentine Valley, and several miles of corduroyed track under a few inches of water, to the river. We had intended to sleep at the “Florrie Huts,” but found them occupied, so we left our bespattered bikes and pushed on for the Gordon Bend, feeling tired and shoulder-sore and rather low. But the sunset tipping the Thumbs with gold was glorious, and the rain added intensity to the purple and green of their mass.

We went through dripping myrtle forest, floundering from moss to mud, across the low Gordon Range until the Rasselas Valley opened out in front of us, and we saw in the far distance the Gordon Bend, with the hills seeming to converge like a series of veils. It must be best to approach the Gordon by daylight, though it might lose something of the sense of mystery (by day, too, of course, there is the fun of collecting bones from the litter of skeletons, which suggest that the local fauna die with their boots on). We paddled along a track worn down below the level of the plain, and filled with water, or as an alternative we stumbled alongside through the scrub. We felt rather nervous as our objective faded to a dark shadow in the darkness, without our seeming to get any nearer; but at last we splashed up to the hut, at about 10 pm. After struggling with a wet fire long enough to heat soup and stew, we tumbled into the bed — ten feet square and mattressed with sword-grass — without looking for snakes; and slept the clock round.

So much for our resolution to make an early start! The morning, when we inspected it at 11 o’clock, was warm and sleepy. The bridge over the Gordon seemed an ideal place for breakfast, and we sat there till noon, bemused by the dazzle of sunlight on a line of rapids, listening to the gurgle of brown water over the stones, and the song of birds in the gum-trees. The rest of the trip was pleasant walking — part button-grass, part through an open forest of very slender tall trees with the river running unseen not far away, and thrushes and pallid cuckoo answering joyfully to our whistling.

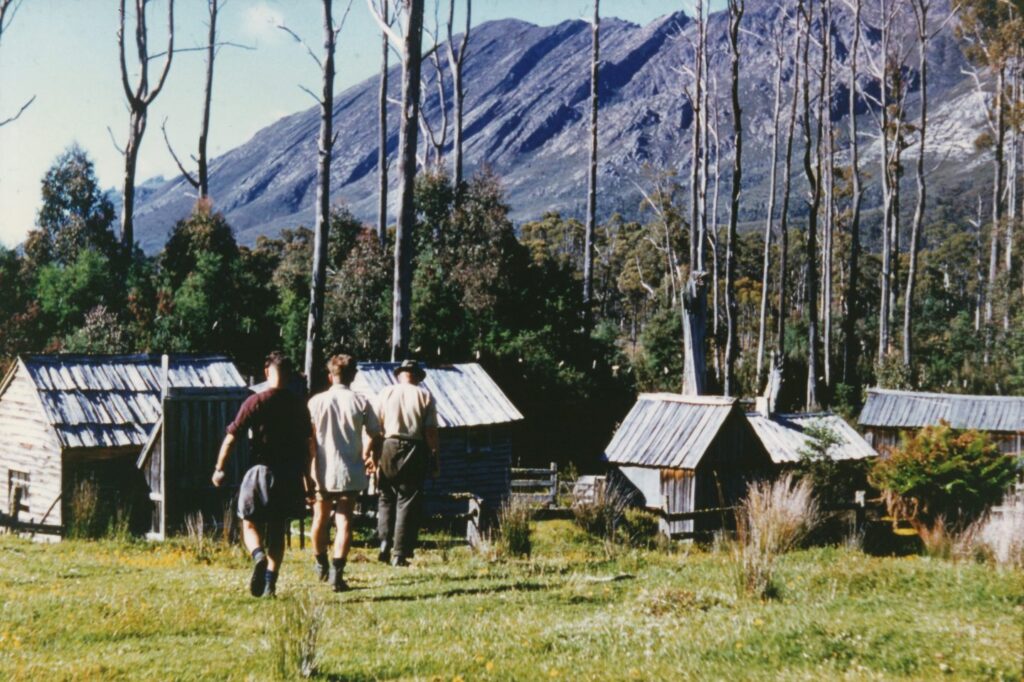

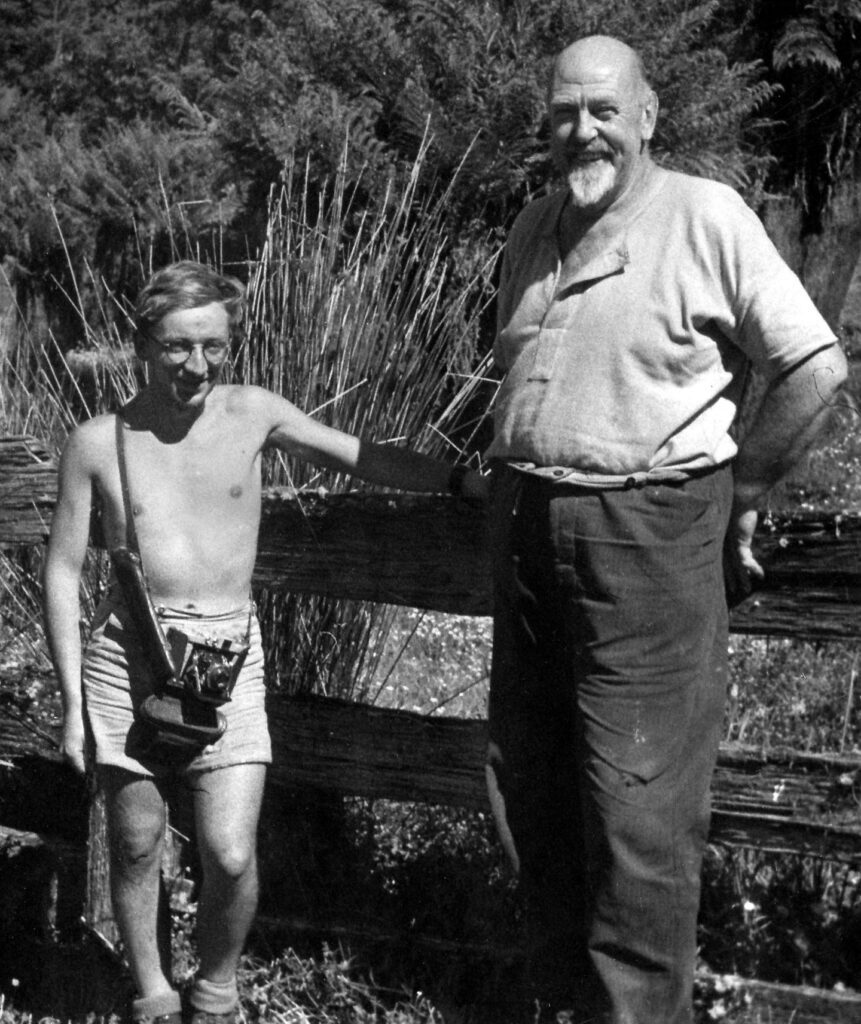

The track is dominated on the western side by the razorback range of Mt. Wright, savagely scarred with gullies. At the far end — about seven miles from the Bend — is Ernie’s “place.” It’s not a shack, it’s a model village. It even has a dairy — you can’t help feeling for the cow, who must have puffed wearily all the way up from the Florentine only to find herself alone with the roos and the devils. But we were grateful to her: we had cream with our new bread and honey, and cream with the raspberries picked from the most luxurious kitchen-garden I have ever known.

Next day we climbed Mt. Wright — went up the wrong gully and hung on by our fingers to a precipitous rock face, with cold fear in our hearts and empty air wheeling beneath. But the joy of skylining along the top, with the vision of mountains westward, was sufficient compensation. Looking down, the valley appears park-like — the troublesome button-grass seems to be mown and rolled turf, and the tangled scrub is a well-kempt thicket. To the east, Field West stands up salmon-pink in the afternoon light, buttressed like a cathedral.

I’d like to spend a month in the Rasselas Valley. As it was, we had only one day for exploring the Denisons, which lie along the nor-west horizon; and the King William Range, even more remote and beckoning, was quite outside our orbit. They say that on a frosty night in winter, the Denisons under snow look as if you could reach out and touch them: in midsummer as we saw them, they are pale mauve, magically traced, and seemingly veiled-off from the world of reality. We thrust our way up the valley to their base, following wallaby and roo tracks where possible, through dense trees and knee-high grass, where every step we expected to tread on a snake. Then climbed up over steep slopes, and followed a well-defined track along a ridge — animals are energetic — and looked straight on a circular lake, rich red-brown with a strip of gleaming quartz sand. And facing us, higher by far, was Read’s Peak, magnificent and jagged and beautiful, looking as if it would fall forward on top of our world. The Peak has a great rift from top to bottom, a rift with a metallic silvery gleam at the top — was it a waterfall or was it osmiridium?

It’s a pity we didn’t have enough time or energy to explore the peak that day (as it was, we arrived “home” so weary that a draught of Ernie’s honey-mead skittled us). It’s a pity we didn’t have time to camp by the lakeside, and swim every morning among the startled anaspides, and explore the wonderful Denisons, to our heart’s content.

Banner image: Matthew Newton